Humans often boast that they are the only mammals on Earth that know how to grow food. 10,000 years ago, with the advent of primitive agriculture, our ancestors solved hunger.

Abundant food sources have since allowed humans to increase their population, strengthen their nutrition to grow both in height and weight. There is no denying that farming and agriculture have contributed greatly to the development and prosperity of human civilization.

That is why in games that simulate the development of civilizations, such as Empire, the activity of drawing fields and growing food in the second generation instead of hunting and gathering has always been emphasized.

But now, there is the first non-human mammal that seems to know how to do it too. In a new study published in the journal Current Biology, scientists suggest that gophers, or American pocket mice, may have also practiced agriculture.

These pocket mice love to eat the roots of longleaf pine trees. As a result, they often burrow beneath fields or forests where these trees grow. But gophers don’t just harvest the longleaf pine roots that grow into their burrows; they also grow new roots to eat.

The mice create their own farming areas within their burrow systems, which are often hundreds of meters long and filled with winding tunnels. They also store urine and feces, which they use to fertilize the roots to increase productivity.

While there is some scientific debate over the definition of farming, and whether the behavior of pocket mice constitutes farming, the authors of the new study point to some clear signs that these mice have managed agriculture, at least in the same way that humans manage forests.

Biologist Francis Putz from the University of Florida states, “Southeastern pocket gophers are the first non-human mammals to engage in agriculture. Previously, agriculture was known to be practiced only by ants, beetles, and termites, not by any other mammals besides humans.”

You may not know, but many animals also practice agriculture

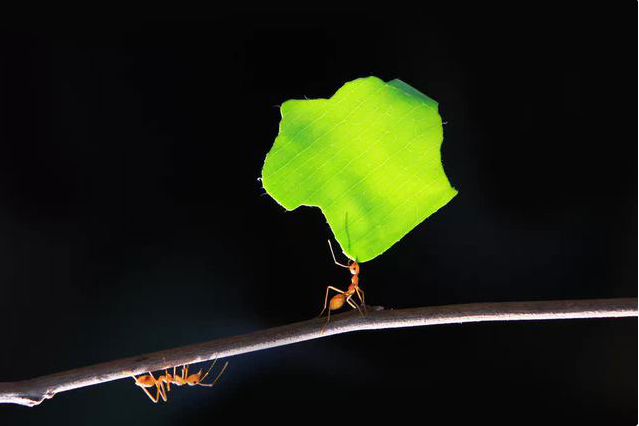

That’s the case with some insects, such as ants. Leaf-cutter ants (Atta, Acromyrmex) in Central and South America are known for their ability to farm fungi. Many people mistakenly believe that these ants cut leaves to bring back to their nests to eat. But no, that’s just their source of food.

In the forests of Mexico, you can easily see these ants carrying leaves, grass, and sometimes fresh flowers back to their nests that are 20 times larger than their bodies. The purpose is to feed the fungi they are farming.

The ants wait until the mushrooms have grown before eating them. This is because mushrooms are more nutritious than leaves. Although this is a smart strategy, sometimes the ants fail. If their mushroom farming business is difficult, the leaf cutter ants can face starvation in the colony.

Another species of ant, the black garden ant (Lasius niger), has a farming strategy that takes the form of livestock farming. These ants raise aphids inside a system of cages that they design, similar to the way humans raise dairy cows. The goal is to “milk” the aphids’ honeydew, a source of sugar and nutrients for the ants.

Black garden ants literally graze aphids. They often designate an area of tree branches that is most nutritious for the aphids to live in, while guarding them to protect them from predators.

On winter evenings, the ants also carry the aphids into their nests to keep them warm, then herd them out during the day. To keep aphids in the meadow from flying away, some ants clip their wings.

Black garden ants also keep aphids’ eggs, so that when they arrive in a new area, these eggs can hatch into a new colony of aphids, to breed there. But the most interesting part is that ants know how to train aphids to milk their own milk.

Well-trained aphids will fill up with honey until the ants stroke them with their antennae, at which point they will secrete milk. Perhaps with these sophisticated skills, ants must have been the first civilization on Earth to learn how to farm, not humans.

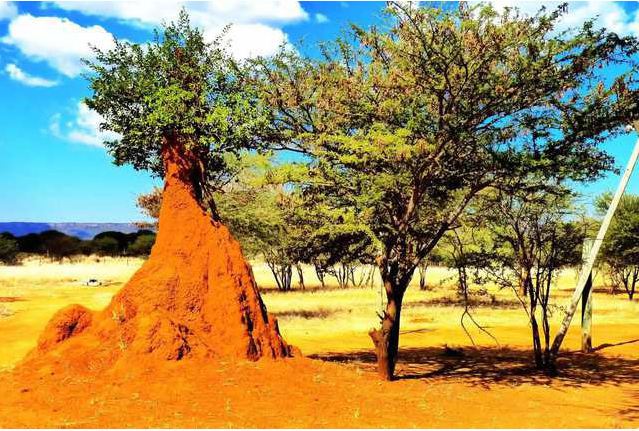

Back to crop-based agriculture, we also have termites that grow mushrooms. Termite nests are often designed with complex mounds of earth, with several chambers that are temperature and humidity controlled to allow mushrooms to grow. Like leaf-cutter ants, termites grow mushrooms in these chambers for food. They collect leaves and wood to chew on for the mushrooms to grow.

Ambrosia beetles also cultivate fungi in a similar way. They manage their crops inside the rotting bark of trees. Many people also mistakenly believe that these termites bore into trees and eat wood. But no, the sawdust they chip off the wood is just to feed the fungi. Both adults and nymphs of Ambrosia beetles feed on fungi.

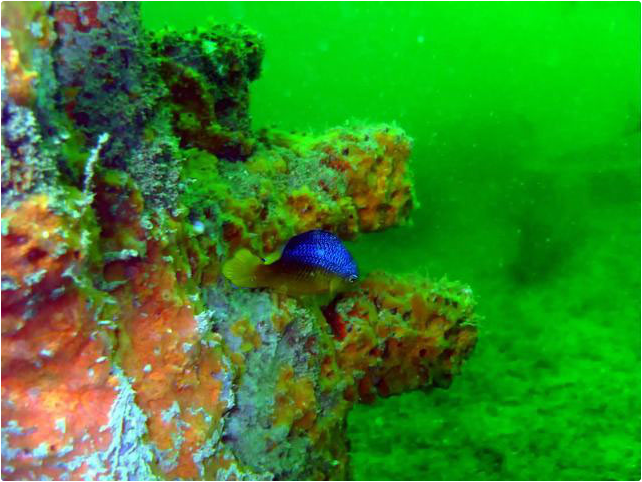

Another fungus-farming species is the Marsh Periwinkles (Littoraria irrorata). They are also known for cultivating parasitic fungi on grass leaves. The snails use their rough tongues to carve deep grooves in the leaves, like a plowshare. The fungi can then grow inside those grooves. The snails defecate in the grooves every day to fertilize their crops.

Underwater, you can expect fish-based agriculture. Dam fish are known to cultivate algae. They tend their algae fields and defend their territories fiercely. These fish often attack anything that swims near their crops.

But now, scientists have found the first mammal that knows how to grow crops

So while agriculture is not an inaccessible aspect for many insects, mollusks, and crustaceans, it is a relatively new concept for mammals, not humans.

Even the intelligent large apes that are closely related to us are still limited to foraging societies. But now there is a species of kangaroo that can grow crops.

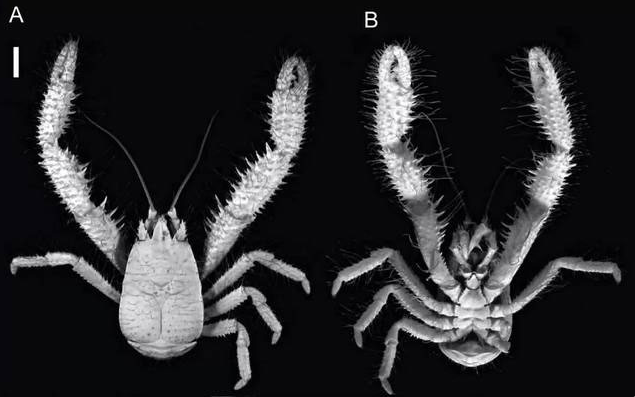

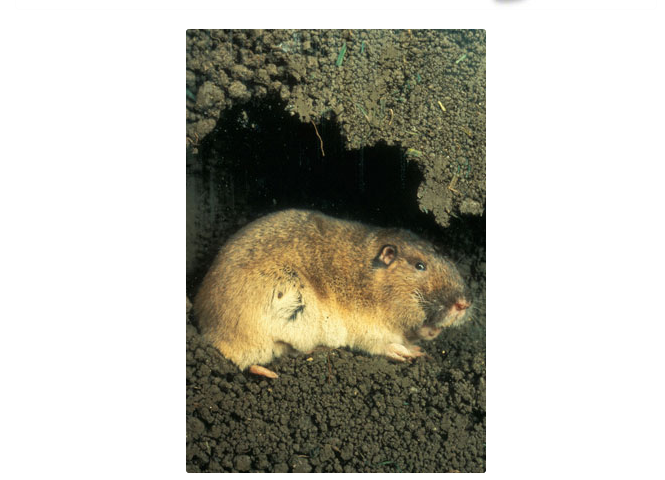

That is the Gopher (Geomys pinetis), a small marsupial mouse that lives in North and Central America. They weigh only about 200 grams, are 15-20 cm long, and have grayish-brown fur. The gopher’s most powerful tool is its large teeth and claws, which it uses to dig burrows beneath fields to eat plant roots.

Gophers spend most of their lives underground, digging tunnels as large and long as a football field. They only surface occasionally during mating season.

To learn more about the gopher’s habits, University of Florida biologist Francis Putz traveled to the Flamingo Hammock Trust, a rural, communally managed property that Putz owns part of, to study.

He and his undergraduate students used an endoscope (the kind used to inspect plumbing and car engines) to peer inside the gopher’s burrows. Observing the species’ social life, Putz found that the gophers not only ate plant roots, they also grew crops.

Specifically, gophers often harvest the roots of longleaf pine or nettles that grow into their tunnels. After harvesting, they will urinate and defecate throughout the tunnels as a form of fertilizer for the roots to grow longer.

This waste will create a dense environment of moist air and rich in nutrients that stimulate the roots to continue to grow. Through fertilization, American gophers can grow enough roots to provide 20-60% of their daily caloric needs, and only need to find new roots in the remaining area.

Although this is not a sophisticated form of farming, researchers believe that the behavior of gophers is similar enough to the way humans manage natural forest areas, including harvesting crops with restraint, saving and caring for a portion of it for future growth.

Putz notes that in most cases, the pocket gophers don’t drag the entire plant into their tunnels and eat it. They always leave some behind to feed their roots.

This activity requires both time and energy. The gophers are also protective of their crops.

“They’re trying to create the perfect environment for the roots to grow and fertilize the crop,” says zoologist Veronica Selden at the University of Florida. “All of these conditions are part of a low-level food production system.”

The recent research has been published in the journal Current Biology.